The translation of The Dialect of the Tribe in French

| "The Dialect of the Tribe" | |

|---|---|

| Short story by Harry Mathews | |

Harry Mathews, 2004. | |

| Translator | Martin Winckler (1991) |

| Language | English |

| Publication | |

| Publication date | 1980 |

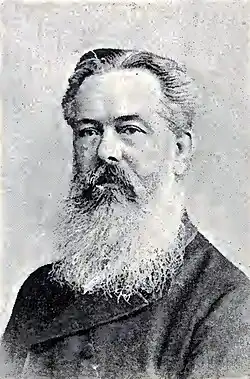

The Dialect of the Tribe is a nine-page humorous short story by Harry Mathews (1930–2017), an American francophone writer, close to Georges Perec, and who joined the Oulipo group in 1973.

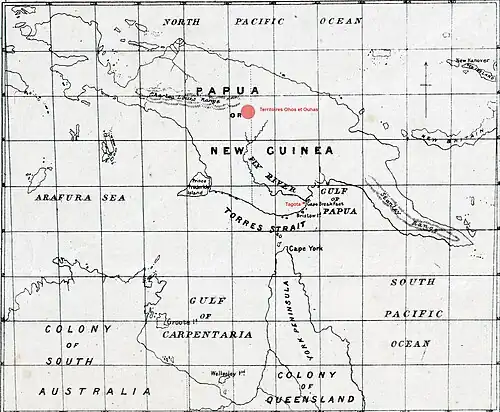

It deals with pagolak, a fictional dialect of an equally fictional mountain tribe in central New Guinea, supposedly studied in the 1920s by the Australian linguist Ernest Botherby (Perth, 1869 – Adelaide, 1944). This language is said to have the peculiar feature of being intelligible to neighboring tribes without them understanding the meaning of the words used. Dictionaries thus prove inadequate for comprehending this phenomenon, as do attempts at explanation, to the point where the narrator, like Dr. Botherby, is left to carry out the process himself — in pagolak. The gradual encroachment of an allegedly scientific discourse by another, incomprehensible one in pagolak, creates a comic effect while questioning the translation process, both regarding the performative nature of the result and the untranslatability of the original.

The original publication in 1980 was preceded by the publication of the French translation of an earlier, longer version of the story, which included several details explicitly referring to the author's relationship with Perec, later removed from the final version. Sixteen years later, Mathews reuses the character of Dr. Botherby in Oulipo et traduction: Le cas du Maltais persévérant (Oulipo and Translation: The Case of the Persevering Maltese) for a report on another ethnolinguistic discovery: the Ohos, whose language is limited to the three words "Red equals bad," and the Ouhas, who also can say only one phrase, "Here not there." Botherby's attempt to explain the Ouhas' language to the Ohos leads him to realize that a language can only say what it is capable of saying. This variant refers to a chapter of Life: A User's Manual by Perec, particularly the story of the Austrian anthropologist Appenzzell and his observations about the allegedly poor vocabulary of the Kubus of Sumatra.

The two versions of The Dialect of the Tribe and Oulipo and Translation: The Case of the Persevering Maltese form an intertextual network of fictions united by the common theme of translation issues and by the character of Botherby, alluding to Perec's underlying text about Appenzzell, to the relationship between Mathews and Perec, and their shared practices of writing and translation. This short story, which has drawn the attention of several translation specialists, has been linked to various theses from analytic philosophy concerning the stakes of translation. It also resonates with the pioneering work of anthropologist Bronisław Malinowski, stemming from his fieldwork in New Guinea. Finally, it illustrates the broader conception of translation within Oulipo, treating it as a particular case-constrained writing.

Intertextuality

The two French versions of the short story

The Dialect of the Tribe was originally published in 1980 in the American journal SubStance[1] and later that same year included, with a dedication to Georges Perec, in the collection Country Cooking and Other Stories.[2] The French translation of this collection, published in 1991 under the title Cuisine de pays, includes a translation by Martin Winckler of the second version of the story, titled Le Dialecte de la tribu.[1]

The original title, The Dialect of the Tribe, is taken from a passage in T. S. Eliot's poem Little Gidding: "Since our concern was speech, and speech impelled us / To purify the dialect of the tribe," where the phrase "to purify the dialect of the tribe" is itself the translation of a verse from Mallarmé's Le Tombeau d'Edgar Poe: "donner un sens plus pur aux mots de la tribu."[3][4] The choice of this title, which also echoes Baudelaire's translation of Poe, signals to the reader the central importance of the theme of translation in the story.[5]

The first publication in English was preceded, not without relation to the translation theory issues raised by the text,[6] by the 1979 publication of a French translation by Marie Chaix, in a special issue of the journal L'Arc (magazine) devoted to Georges Perec. This was the first, longer version of the story, titled Abanika, traditore?, referring to the Italian phrase traduttore, traditore ("translator, traitor").[7] Martin Winckler, the translator of the second version published by Éditions P.O.L in 1991, recounts that this was the first translation project entrusted to him by Paul Otchakovsky-Laurens, "as a trial," and adds that the text had previously been translated by Georges Perec himself.[8] As Dennis Duncan points out, the translation published by L'Arc is by Marie Chaix,[6] and concludes, in pagolak, the Papuan language central to the story, with the phrase "Nalaman: Chaixan Marianu," where the pagolak term nalaman designates the translation, or more precisely "the final result of the [translative] transformation."[9]

The 1979 longer version multiplies explicit references to Perec. It is presented in the form of a letter addressed to "My dear Perec" ("Pereca Georgean" in Pagolak) and signed "Mathewsu Harryan." It mentions Mathews's translation of Perec's autobiographical text Les Gnocchis de l'automne,[10] by homophonic reference to the Greek precept gnothi seauton ("know thyself"), and refers to the text on Roussel co-written by Perec and Mathews,[11] with the comment: "Although the New Guinea text has nothing to do with him, our perverse Raymond would certainly have been intrigued by Pagolak."[12] All these mentions evoking a personal dimension are removed in the second version,[13] which, apart from the dedication (present only in the English version), limits itself to referencing the narrator's participation in a Festschrift (a collection of scholarly writings) in honor of the recipient — this detail serving to reinforce the ostensibly scientific character of the text.

Dr. Botherby

The Dialect of the Tribe, just like its first version, Abanika, traditore?, revolves around the narrator's discovery—thanks to Miss Maxine Moon,[N 1] the librarian of Fitchwinder University[N 2]—of an article by Dr. Botherby about the language of an isolated New Guinea tribe, the Pagolak.

However, the story provides very little information about the supposed discoverer of Pagolak, limiting itself to mentioning "a certain Ernest Botherby (bless him!)" referred to as "doctor."[16] The name Botherby is likely a nod to Bartlebooth, the character from Life: A User's Manual (La Vie mode d'emploi), who himself refers back to Herman Melville's Bartleby and Valery Larbaud's Barnabooth,[17] but also to Borges' Dr. Brodie, who, like Gulliver, encounters the Yahoos.[18] Botherby's Australian nationality, in turn, through a marked homophony in English where Australia and Austria sound very close, evokes the character Marcel Appenzzell, an Austrian anthropologist in Life: A User's Manual, with whom he shares youthfulness, a taste for solitary explorations, and (implicitly in Mathews's work) a filiation with the works of Bronisław Malinowski.[18]

Beyond the alliterative reference to Appenzzell's native Austria, the choice of Australian nationality for Botherby also helps create a pseudo-scientific realism effect, since ethnolinguistic studies in New Guinea were largely conducted by Australian scientists. Such studies developed after the establishment of the Australian mandate over New Guinea and especially after World War II, whereas the ones from the interwar period were mainly strictly ethnographic, carried out by anthropologists without linguistic training and therefore only produced "naive observations of little [scientific] value."[19] The first rigorous work on the languages of the Sepik Basin — the region supposedly explored by Botherby — was undertaken by the Australian ethnolinguist Donald Laycock in the 1959–1960 period.[19] Moreover, in a 1961 article, Laycock emphasizes the importance of distinguishing between language and dialect in the linguistic context of the region. He considers that the term "dialect" should be reserved for variants of a language that do not prevent communication between speakers and that it should not be used for an oral language without a written tradition, nor for a local language differing from the official one.[20]

Mathews adds a few details about Ernest Botherby in another text published in 1997 and translated into French in 2013, Oulipo and Translation: The Case of the Persevering Maltese.[7] Ernest Botherby, born in Perth in 1869 and died in Adelaide in 1944, was "the scholar who founded the Australian school of ethnolinguistics," for whom "the tribes of New Guinea" were "a favorite subject," and who "rose to fame in the late 1920s after publishing several articles" on Pagolak.[21] A specialist in New Guinea tribes and particularly interested in those who had fled all contact with their neighbors, he began anthropological research at the age of twenty-four, basing his work on that of NIcholas Mikloukho-Maclay, one of the first explorers of New Guinea, Samuel Macfarlane, who explored the Fly River, and Friedrich Hermann Otto Finsch, who explored the Sepik.[22]

Ohos and Ouhas

Botherby's first exploration, reported in The Case of the Persevering Maltese, takes place in the area of the central highlands of New Guinea, near the source of the Fly River.[22] Mathews provides details inspired by travel accounts from the late 19th century, such as that of Samuel Macfarlane:[23][N 3]

Leaving from Tagota at the mouth of the Fly [River], Botherby traveled upriver for more than 500 miles [...] to finally reach the unexplored region he sought, a set of valleys located — using the toponymy of the time — between the Kaiserin Augusta, the Victor Emmanuel ranges,[N 4] and the extension of the Musgrave range.[22]

It is the most linguistically complex region of New Guinea (itself considered the most diverse region in the world in this respect, as nearly 1,000 languages are recorded there, often showing "enormous variation and many unusual features"[26]), where even today, about a hundred Papuan languages, highly heterogeneous, are spoken.[27] In a mountainous valley, Botherby discovers an archaic tribe of "a few hundred individuals, leading a peaceful existence under conditions of extreme simplicity."[22] He names them the Ohos. Their language is reduced to three words and a single expression: "Red equals bad," although they make up for the poverty of their vocabulary by communicating through gestures, notably to indicate directions to Botherby or to express disagreement.[28]

Continuing his exploration, Botherby discovers a second archaic tribe, which he names the Ouhas, whose language, just as rudimentary as that of the Ohos, only allows them to make "invariably the same statement": "Here not there."[29]

A few weeks later, back in the Ohos valley and wishing to share his experience with them, he understands "what every translator learns sooner or later: a language says what it can say, and that's all."[30] Thus, he has no choice but to translate "Here not there" as "Red equals bad."[31] This extreme experience allows Mathews to "playfully contradict" Jakobson's assertion that "languages differ essentially in what they must convey and not in what they may convey."[32]

Pagolak

Le Dialecte de la tribu (French translation), although published earlier, deals with events occurring after the discovery of the Ohos and the Ouhas. This time, it concerns another tribe of New Guinea, speaking a language called "pagolak." The short story takes the form of a letter in which the author reports his discovery of this language after reading a scientific article attributed to Dr. Botherby and titled Kalo gap pagolak, a title meaning "magical transformation of the pagolak." Botherby's article discusses the method used by the tribe speaking pagolak to translate expressions from their language into that of their neighbors—a method that produces translations that are "effective,"[12] "intelligible and acceptable,"[16] while hiding "the content,"[12] the "primary meaning"[16] of the original statements. The kalo gap pagolak is more precisely the transcription of an oral statement by the abanika, the "chief of the word-chiefs"[35] or "Chief of the Chief-Words"[36] of the tribe, although the faculty of translation is not reserved for him: all members of the tribe who speak pagolak are capable of it.

Although pagolak is a "very primitive,"[12] "rudimentary" language,[36] and although there are two dictionaries (one English, the other Dutch), these dictionaries, intended for traders, are arbitrary:[36] they take into account only mercantile criteria[37] and are of no use for understanding the translation method addressed in the kalo gap pagolak. Botherby himself, although providing "useful"[38] and even "very valuable" notes,[37] has "no other choice but to leave the abanika's statement intact"[38] and provide no translation for it[37]—a solution the narrator eventually applies to his letter.

The abanika's statement is not made up of "words about a [translation] process" whose "substantial content" would need to be explained, but rather of "the words of the process in action;"[37] it is not "a description of the method, but the method itself."[37] As a result, the narrator, following Dr. Botherby, claims he is capable of understanding the kalo gap without being able to reproduce it in another language. This "hermetic transformation"[9] performed by the speaker of pagolak is apprehended through the terms namele and nalaman, which respectively designate the means of the transformation and its result—the transition from one to the other giving rise to a "subtle redistribution of phonemes,"[35] a "first demonstration" of the kalo gap, of the "transformative magic" at work.[9] The awareness of the kalo gap is part of the rites of passage into adulthood, called nanmana, which is itself equated, through a "magical pun," with the transformation of the language (namele).[35] The central ritual moment is sitokap utu sisi, meaning "reinstall words in (own) eggs,"[39] with the young people emerging from childhood "like seagulls hatching from hens' eggs."[35]

Tribute to Perec

As Mariacarmela Mancarella observes, the presence of Dr. Botherby in the two translated versions of The Dialect of the Tribe and then in The Case of the Persistent Maltese makes this character a sort of common thread, inviting consideration of transtextuality by revealing the "hypertextual" nature (the concept of hypertext is defined by Gérard Genette as the status of a text derived from another one—the hypotext—and which invites a "relational reading," a connection between the two texts[40]) of Dialecte de la tribu, d'Abanika, traditore?, and Oulipo et traduction: Le cas du Maltais persévérant, concerning a "hypotext," Life: A User's Manual.[41]

Le Dialecte de la tribu is, in its original version, dedicated to Georges Perec. The dedication to Perec in the first edition of The Dialect of the Tribe and the numerous references to him in the draft version not only reflect the friendly bond between the two writers but also underline the importance of their collaboration, beyond the article on Roussel et Venise. Perec notably translated two of Mathews' novels, Les Verts Champs de moutarde de l'Afghanistan (The Green Fields of Afghanistan's Mustard) and Le Naufrage du stade Odradek (The Sinking of the Odradek Stadium); according to Duncan, a scene from Mathews' novel Conversions is reproduced in Chapter 27 of Life: A User's Manual, which Mathews, in turn, translated for an English-language anthology.[42] Thus, the insertion of The Dialect of the Tribe in the context of an exchange with Perec discreetly testifies to a privileged relationship,[41] prompting Dominique Jullien to remark that "the intertextual relations between Georges Perec and Harry Mathews [...] would certainly deserve a full study of their own."[43] Moreover, in an interview with Burhan Tufail, Mathews acknowledges that he may have been too discreet and that this very discretion may have disappointed Perec: "Alas, he did not fully realize that it was a tribute to our relationship. I think he was disappointed that the connection to his work was not more explicit."[41]

The character of Dr. Botherby thus refers to a chapter of Life: A User's Manual devoted to Appenzzell, an Austrian anthropologist "trained at the school of Malinowski," who, at the age of 23, left for Sumatra in search of a "phantom people that the Malays call the Anadalams, or the Orang-Kubus, or simply the Kubus."[44] Appenzzell gradually realizes that the Kubus he wishes to observe flees from contact with him and that he is the cause of their flight. After six years, Appenzzell must give up his project and return to Europe, having, Perec notes, "practically lost the use of speech."[44] This chapter of Perec's novel draws upon an earlier work of his: the writing in 1975 of a commentary for Daniel Bertolino's documentary Ahô: The Forest People,[45] a commissioned work for which Perec, according to his biographer David Bellos, had to read and write about the Kubus of Sumatra and the Papuans of New Guinea.[46] The documentary presents the former as "specialists in avoiding"[45] the white man. Perec commented in 1981: "This story deeply moved me because it exemplifies the anthropological approach: if you want to go observe the 'savages,' they, on the other hand, have no desire to be observed! So I decided to write a fiction about it."[47]

Questions of translation

The issue of translation is central to the texts featuring Dr. Botherby, beginning with The Dialect of the Tribe. From the very first paragraph, the narrator evokes "the question of translation in general," and in particular that of Perec's works. He asserts: "Translation is the model, the archetype of all writing."[48] Furthermore, the second version includes an addition compared to the first, which Mariacarmela Mancarella considers "particularly significant:"[49]

How to translate a process? One would have to convey not only the words but also the silences between them... as if trying to photograph the invisible air under a wing's beat in mid-flight. Impossible.[9]

Mancarella sees in this a reference to the last sentence of Walter Benjamin's The Task of the Translator:

In some degree, all great writings, and most profoundly the sacred writings, contain their virtual translation between the lines. The intralinear version of the sacred text is the archetype or ideal of all translation.[50]

This fundamental issue is addressed from another angle in the first version of the story:

You and I are well placed to know how false this [notion of communication of a substantial content] is and how translation, precisely, is an example of 'non-communication,' an act that, in fact, dispels the illusion of substantial content.[37]

These statements suggest that the issue in the text is interlingual translation, the translation from one language to another. Emily Apter considers that the story points to one of the "truisms of translation," namely that something is always lost in translation and that, unless one "knows the language of the original, the exact nature of the loss will always be impossible to establish, and even if one has access to it, there is always an incompressible remainder of untranslatability that makes every translation an impossible world, a false regime of semantic and phonetic equivalence."[51] Furthermore, as Alison James emphasizes, in the case of translating Ouha into Oho, it is interlingual translation from one language to another that is at stake, with Mathews seeming concerned with "the inevitable transformation of meaning in the passage from one language or culture to another."[52] For his part, Dennis Duncan, drawing on Emily Apter's reading, considers that the fable of pagolak deals with the same subject as that of the Ohos and the Ouhas—the "incommensurability"[53] of every language and the impossibility of translating it into any other language, "into English, French... or middle Bactrian."[38]

Relationship to Quine and Wittgenstein

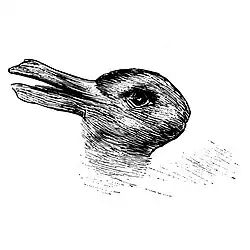

Several authors believe that Dr. Botherby's experiences evoke or illustrate Quine's analyses on the indeterminacy of translation.[52][54] Quine, in Word and Object, asks the question: "How can the linguist know that his translation is correct?" However, Mathews would substitute this question with: "What happens if the linguist knows that his translation will always be wrong?"[53] Quine develops his analysis on this issue through what he calls the thought experiment of radical translation, illustrated by the example of the word gavagaï spoken by a native in the jungle at the emergence of a rabbit. The linguist, attempting to understand what this word means, ends up associating it with the observational statement "look, a rabbit," which can be confirmed by the assent of his interlocutor, yet the term does not lose its inscrutability.[55] Quine observes, it is unclear whether "the objects to which the term applies are not, after all, something like rabbits, for example, simple phases, brief temporal segments of rabbits... or perhaps the objects to which 'gavagaï' applies are only the parts, the still undivided pieces of these rabbits."[56] Quine notes that two independent dictionaries of this native language could present different and interchangeable content, each proposing a translation that the other would reject, while still describing the same behavior,[57] which resembles the difficulties encountered in using the two dictionaries of pagolak. Furthermore, Dr. Botherby's disillusioned statement about the difficulty of translating the Ouhas' claim, "Here, not there," into the language of the Ohos, which can say "Red equals bad," seems to echo Quine's remark: "Who would attempt to translate 'neutrinos lack mass' into a jungle language?"[58]

Mark Ford and Dennis Duncan, for their part, suggest that both the attempts at translating pagolak and the ouha in Mathews' works and Perec's notations about the Kubus resonate with Wittgenstein's reflections on language games.[34][59][N 6] Perec reports an incidental remark by Appenzzell about the poverty of the Kubu vocabulary, exemplified by the polysemy of the term sinuya: "These characteristics could apply to a Western carpenter, who, using instruments with very precise names... would ask his apprentice: 'Pass me the thing.'[44]" This allusion, which the context of the novel does not require,[62] refers, for Ford and Duncan, to a passage from Philosophical Investigations where Wittgenstein proposes a model of the "entire language of a tribe," aiming to "dispel the fog by studying the language phenomena in the primitive forms of their usage that allow for a synoptic view of the purpose and function of words." This "complete primitive language" consists of four words used in exchanges between a mason and his apprentice: "block," "column," "slab," and "beam,"[63][64] with the carpenter's injunction in Perec echoing the mason's command in Wittgenstein: "Slab!" for "bring me the slab!"[62] For Duncan, it is "immediately apparent" that the example of the Ohos and Ouhas is intended to perform a "dispelling of the fog," a modeling of the type Wittgenstein sought to carry out.[65]

Relationship to Malinowski

.jpg)

Marcel Appenzzell, the character in Life: A User's Manual to whom Mathews' Dr. Botherby refers, is presented by Perec as a student of Bronisław Malinowski, with whom he maintains correspondence and through whom he is introduced to Marcel Mauss,[N 7] "who entrusted him at the Institute of Ethnology with the responsibility for a seminar on the ways of life of the Anadalams."[44] In contrast, the short stories by Mathews where Dr. Botherby appears do not explicitly refer to Malinowski, but the connection is suggested by several clues: the period of scientific activity (the 1920s), the field (New Guinea[N 8]), and the translation issues that Mathews places at the center of the texts where Botherby appears. Moreover, both Quine's and Wittgenstein's analyses of language, which lead the former to employ the model of gavagaï and the latter to that of the mason, are inspired by or linked to Malinowski's analyses. Quine explicitly refers to these in Word and Object,[69][70] and Ernest Gellner emphasizes the proximity of Wittgenstein's analyses in Philosophical Investigations to the earlier thesis by Malinowski, which Wittgenstein may have encountered through Charles Kay Ogden, his English translator.[71][N 9]

Malinowski provides a general formulation of his analysis in Le problème de la signification dans les langues primitives (The Problem of Meaning in Primitive Languages), a text published in 1923 as an appendix to the book The Meaning of Meaning by Ogden and Ivor Armstrong Richards, in terms that resonate with Dr. Botherby's considerations on the uselessness of dictionaries for understanding pagolak. He asserts that the available vocabularies of Oceanic languages, which at his time were primarily written by missionaries with the intent of helping their successors, limit themselves to providing the best possible approximation of a local term, without aiming, as a scientific translation would, to determine whether a word corresponds to an idea in the reader's language or whether it corresponds to a completely foreign concept. This is the case with beliefs, customs, ceremonies, or magical rites, for which it would be necessary to provide an "imaginary equivalent" and clarify its meaning through an ethnographic explanation. Malinowski further asserts that in these languages, the use of metaphors, abstractions, and generalizations, combined with the concrete nature of expression, makes any simple and direct translation of words taken in isolation almost impossible, which leads him to develop the notion of "phatic communion," a situation where social ties are created through the exchange of words and, consequently, the role of language in social interaction, emphasizing the importance of the position of words and the context of their usage.[73] These analyses are developed in Coral Gardens, where he claims that the words of one language are never translatable into another[74] and that the difficulty of translation increases with cultural specificities: "sport for England, good food and love-making for France; sentimentality and metaphysical depths for Germany; music, pasta, and painting for Italy."[75] He therefore concludes that "if we understand 'to translate' as finding verbal equivalents between two languages, this task is impossible, and the Italian proverb Traduttore, traditore is true."[76] However, a translation is possible and correct if understood as cultural contextualization, and more specifically, as making the meaning of a word understood as the "effective change" it brings to a situation.[77] As Bertrand Gervais points out, these aspects of phatic communication and performative value are precisely those that take precedence over the denotative function in both the Ohos and Ouhas, as well as in pagolak.[78]

A section of Coral Gardens is dedicated to a problem similar to the one Botherby encounters with pagolak: the translation of magical formulas. Malinowski opts to render them in a "rhythmic and elaborate English version of the indigenous text," believing that "in the original version, the magical language, with its wealth of phonetic, rhythmic, metaphoric, and alliterative effects, with its strange cadences and repetitions, has a prosodic character that must be conveyed to the reader," without, however, taking too many liberties with it. He summarizes the difficulty as the translation of words that lack meaning, or more precisely, words whose function is not linked to their meaning but to a "magical influence that these words are supposed to exert."[79] Emphasizing that, in line with his theory of "phatic communion," the meaning of any utterance is "the effective change it is supposed to bring about in the context of the situation in which it is uttered,"[80] Malinowski highlights two aspects that guided his approach: the "coefficient of strangeness," which he also calls the "element of nonsense,"[81] meaning that some words are intended not to be understood, and are therefore intrinsically untranslatable; and the "coefficient of intelligibility," meaning that some words belong to everyday language and are intended to be understood.

The strangeness largely consists in an artificial form, in the non-standard use of certain roots, in repetitions or pairings [...] The coefficient of intelligibility resides in the fact that the strangest formulations refer directly or indirectly to the subject on which the magic is focused.[82]

Trope of poor vocabulary

In Life: A User's Manual, the reference to Malinowski primarily serves to give a sense of reality to Appenzzell's desire for exoticism, embedding it within the context of the participatory observation method[83][84] Malinowski develops in The Argonauts of the Western Pacific,[85] even though Perec's ethnological reference may rather be the Lévi-Strauss of Tristes Tropiques.[86] More generally, Perec shows a particular interest in applying an anthropological approach to daily life in his writing practice:

Perhaps it is about finally founding our anthropology: one that will speak of us, that will look within us for what we have long plundered from others. Not the exotic, but the endotic.[87]

However, as Isabelle Dangy observes, this privileging of the endotic does not exclude, in a fictional context, the use of a "fictive, utopian, and semi-parodic ethnology"[88] such as that developed in W or the Memory of Childhood, completed in 1975 just before Perec went to Montreal to collaborate on the commentary of Ahô: The Forest People. Furthermore, as he claims in a 1976 interview, Perec believes that scientific knowledge plays a limited role in the development of his fictions, where it intervenes "not as truth, but as material, or machinery, of the imaginary."[89][90] From an ethnolinguistic perspective, Appenzzell's considerations are particularly close to the situation described by Botherby with the Ohos and the Ouhas: the Kubus, notes Perec's ethnologist, use "an extremely reduced vocabulary, not exceeding a few dozen words,"[44] a fact that leads Appenzzell to wonder whether, "like their distant neighbors, the Papuans,"[44][N 10] the Kubus do not "deliberately impoverish their vocabulary, eliminating words each time there is a death in the village. One consequence of this fact is that a single word designates an increasingly larger number of objects."[44] This observation is a reference to A Void, where Perec quotes on the last page, among other quotes termed "metagraphs," a 1937 geography manual by Étienne Baron:

Among the Papuans, the language is very poor; each tribe has its language, and its vocabulary is constantly impoverishing because, after each death, some words are eliminated as a sign of mourning.[92]

Perec probably read this quote from Barthes, who presents it in 1966 in Critique and Truth while commenting:

On this point, we can teach the Papuans a lesson: we respectfully embalm the language of deceased writers and refuse the words, the new meanings that come into the world of ideas: the sign of mourning strikes here the birth, not the death.[93]

This trope about Papuan language, often repeated elsewhere,[94][95] contradicts a consistent note by Papuan language specialists.[N 11] One of the first, Reverend Samuel Macfarlane, countered the then-popular opinion that the Papuans did not have a proper language, pointing out that, on the contrary, their languages are "in some respects superior to ours," including in terms of vocabulary, some of which had words "as precise in their meaning as if they had been defined by Johnson."[97] With this stereotype, Appenzzell diverges from the recommendations of his mentor, Malinowski, who, based on his fieldwork with the Trobrianders, argued that "the multiplicity of uses of each word is not due to any negative phenomenon such as mental confusion, poverty of language, perverse or careless usage."[98]

Malinowski believes that the same word, used in a variety of meanings, "fulfills a very specific function," that is, "to introduce a familiar element into an indefinite situation."[99] To characterize this fact, Malinowski does not use the notion of polysemy or metaphor, but rather the concept of homonymy, asserting that it would be "erroneous to agglutinate all the meanings into a confused category" and condemning the "armchair anthropologist" who assumes a "pre-logical mentality" without "investigating the different meanings [of a word] or examining whether they are not true homonyms, that is, different words with the same sound."[100] This position, however, has been criticized: Edmund Leach describes the "doctrine of homonyms"[101] as a "desperate expedient," and Quine observes that Malinowski, wishing to "spare" the Trobrianders from an accusation of prelogical thinking, multiplies the translations of the same word according to the context to avoid any contradiction.[69][70]

Interlingual or intralingual translation?

If this example is ambivalent, as it contains both an interlingual dimension (the translation of Kafka into French) and an intralingual dimension (the rewriting of it), the intralingual conception of translation, within the same language, emerges in the article Translation from the Oulipo Compendium, where Harry Mathews states that translation is "a central principle of Oulipian research, but not in the usual sense of the term; Oulipian translation techniques are used within the same language, and each technique manipulates an element of the text that has been artificially isolated from the whole, whether it concerns meaning, sound, grammar, or vocabulary."[104][105]

Mathews summarizes his point of view for journalist Lynne Tillman: "Perhaps writing is nothing but a translation — in the end, a translation that doesn't want to be identified as such,"[106] an assertion that carries two aspects: on the one hand, the position of writing as transformation, as manipulation through constraints, an analysis shared within the Oulipo;[107][108][N 13] and on the other hand, Mathews' personal choice not to reveal the constraints he uses, thus giving the impression of "following rules from elsewhere,"[110][111][N 14] much like Raymond Queneau and in contrast to Perec[112] (who, however, does not reveal all of them).[47]

In this sense, according to Bertrand Gervais, Le Dialecte de la tribu "seems to speak, with its practice of the kalo gap pagolak, about interlingual translation, when it only speaks of intralingual translation, which is at the heart of Oulipian practice."[78] In this sense, the narrator's statement can be interpreted in the story: "One could say that, insofar as true writing is a form of translation, the text from which it operates is infinitely difficult since it is nothing less than the universe itself."[16][114] For Gervais, Mathews' story is a trompe-l'œil:

[It] manages to confuse critics and theorists who fall for the illusion of the represented object. Perhaps, due to an expectation horizon exclusively focused on translation and its theories, the artifice proves particularly powerful, and the screen is mistaken for the thing itself. The tribute, with its allusive system, taking the form of a text with ethnological character and a narrative style like Raymond Roussel, has become a realistic text, and the translation has transformed from a metaphor of writing under constraint into a true interlingual translation.[78]

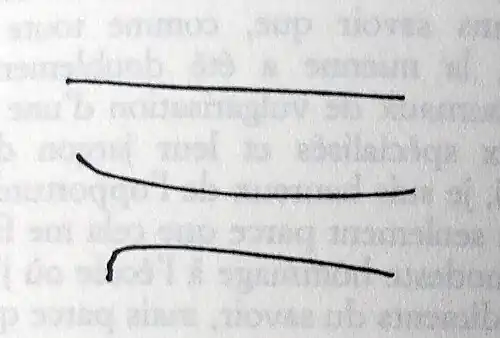

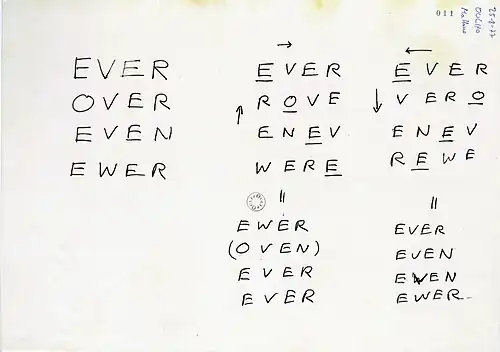

To highlight this dimension of intralingual translation at work in the pagolak, Thomas Beebee emphasizes one aspect: the use of the palindrome.[115] He observes that the very name of the magical method, kalo gap, is a palindrome of pagolak; that the two components of the method, namalam (the end) and namele (the means), are quasi-palindromes; that nanmana (the initiatory rite) is an analogical transformation of namalan; that as the text progresses toward its conclusion, the palindromes become more "monstrous," such as nasavuloniputitupinoluvasan, a large palindrome that contains a small one, tit, in its center; that the final exhortation, which the narrator no longer bothers to translate, is also palindromic; that it again has tit at its center and uses, in at least one sense, all the words of pagolak previously employed:[116]

Amak kalo gap eleman nama la n'kat tokkele sunawa setan amnan wnanisi sutu pakotisovulisanan unafat up lenumo kona kafe avanu lo se akina ba nasavuloniputitupinoluvasan (!!) abanika esolunava efaka nok omunel put afanu nansiluvo sitokap utu sis namu nanmana tes awa nuselek kot tak nalaman namele Pagolak kama.[116][117]

According to Bertrand Gervais, the Oulipian dimension of the intralingual game takes precedence, in Le Dialecte de la tribu, over the apparent discourse regarding interlingual translation: it is not only a tribute to one of the most prominent members of Oulipo, Georges Perec, but also a "self-reflexive" text about Oulipo as a "literary and interpretative community," as a tribe, and about its dialect.[78][N 15] Moreover, as Camille Bloomfield and Hermes Salceda observe, both dimensions of translation, interlingual and intralingual, combine in Oulipian text translation, aiming to "produce in the target language an effect comparable to that produced by the source text in the source culture."[108] This is, for example, the ambition of Umberto Eco's Italian translation of Raymond Queneau's Exercises in Style, about which the translator states: "One must, rather than translate, recreate in another language."[120]

Notes

- ^ This name, whose first name is omitted in the second version, could refer to Maxine Groffsky, Mathews' literary agent.[14]

- ^ This fictitious university, located in Swetham (Massachusetts), a palindrome of Mathews, and mentioned in several of Mathews' novels, in the shared text on Roussel, as well as in Life: A User's Manual and in "53 jours," belongs to the "personal mythology of Perec and Mathews."[15]

- ^ Just like Macfarlane, who lends his name to an orchid, dendrobium macfarlanei [en],[24] Botherby's memory is commemorated by a plant, "the variety of Apégètes known as botherbyi, which was widespread in England before the Great War, when private greenhouses were still common."[21]

- ^ The central mountain ranges were named in honor of King Victor Emmanuel II by Luigi Maria D'Albertis during his exploration of the Fly with Reverend Macfarlane.[25]

- ^ While the narrator of the first state, Abanika, traditore?, focuses on Raymond Roussel.

- ^ Duncan cites, to support this connection, a statement by Jacques Roubaud on the Oulipian author: "He realizes, in an original form, the Wittgensteinian union of language games and forms of life."[60][61]

- ^ Malinowski, whom Mauss visited in London in 1924, maintained correspondence with him and was invited by Mauss to deliver three lectures at the Institute of Ethnology.[66]

- ^ Malinowski's initial project was to choose Central New Guinea as his field of investigation, and it was by a stroke of luck that he ended up replacing it with the Trobriand Islands, an archipelago off the eastern coast of New Guinea.[67][68]

- ^ According to other sources, Wittgenstein's consideration of an "anthropological perspective," that is, the "phatic" or performative dimension of language, is attributed to a "Neapolitan gesture" by his friend, economist Piero Sraffa ("he passed his hand under his chin and asked me: what is the logical form of this?"), which led him to question the thesis of the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus that a proposition is an "image" of the reality it describes.[72]

- ^ Daphne Schnitzer, who considers the passage about the Kubus as a "misplaced metaphor of the persecution of the Jewish people," argues that the spelling "papouas" can be broken down into papas-où?, Thus referring to the absence of the father.[91]

- ^ The treatment of common nouns differs significantly from that of personal names. André Itaenu notes about the Orokaiva: "After death, during the funeral ritual and thereafter, the deceased's personal name is no longer used to refer to them. However, the use of the names of the deceased is not in itself prohibited. Although they are no longer used to refer to the dead themselves, they are commonly used to talk about the living, to tell a story about the dead, to refer to a namesake, in genealogy, or as a name available for a newborn."[96]

- ^ Mathews is also the inventor of the bananagram (from ban and anagram), a humorous term referring to an anagrammatic transformation aimed at "virtually eradicating meaning."[102]

- ^ Perec refers to the "exercises" of lipogrammatic reduction that he undertook for writing A Void as exercises in translation and adds: "The field of translation is a very easy field, because you have a guide, I mean, you have a whole series of things there to help you."[109]

- ^ Perec reports regarding his translations of Mathews' novels that he ignores the "grids" that the latter uses but that he is "forced to know a certain number of them when [he] does the translation, which is an extremely difficult thing and fills [him] with jubilation" when he succeeds.[47]

- ^ Such use of the expression to refer to a group of authors is not the sole domain of Mathews: the expression is used in this sense by Margery Sabin concerning 20th-century fiction writers[118] and by Tim Fulford, more specifically, concerning literary coteries in the 19th century.[119]

References

- ^ a b Mathews & Winckler 1980

- ^ Mathews, Harry (2002). The Human Country: New and Collected Stories. Funks Grove, Dalkey Archive Press.

- ^ James 2008, p. 143

- ^ Conley, Tim; Cain, Stephen (2006). Encyclopedia of Fictional and Fantastic Languages. Westport: Greenwood Press. pp. 42–43. ISBN 978-0-313-02193-0.

- ^ Tufail, Burhan (1999). "Oulipian Grammatology : La règle du jeu". The French Connections of Jacques Derrida. Albany: State University of New York Press. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-7914-4132-9. Retrieved April 28, 2025.

- ^ a b Duncan 2019, p. 125

- ^ a b Mathews & Chaix 1979

- ^ Winckler, Martin (January 10, 2018). "Paul Otchakovsky-Laurens". Archived from the original on January 12, 2020. Retrieved April 28, 2025.

- ^ a b c d Mathews & Winckler 1980, p. 115

- ^ Perec, Georges (1990). "Les Gnocchis de l'automne, ou Réponse à quelques questions me concernant" [Autumn Gnocchi, or Answers to a few questions about me]. Je suis né [I was born] (in French). Paris: Seuil.

- ^ Mathews, Harry (1991a). "Roussel et Venise : esquisse d'une géographie mélancolique" [Roussel and Venice: sketch of a melancholic geography]. Cantatrix Sopranica L. et autres écrits scientifiques [Cantatrix Sopranica L. and other scientific writings] (in French). Paris: Seuil.

- ^ a b c d Mathews & Chaix 1979, p. 73

- ^ Mancarella 2011, p. 55

- ^ Mancarella 2011, p. 62

- ^ Magné, Bernard (1998). Perecollages 1981-1988 (in French). Toulous: Presses universitaires du Mirail. p. 204.

- ^ a b c d Mathews & Winckler 1980, p. 112

- ^ Yvan, Frédéric (2005). "Figure(s) de l'analyste chez Perec" [The figure(s) of the analyst in Perec]. Savoirs et Clinique (in French). 6 (6): 141. doi:10.3917/sc.006.0141.

- ^ a b Duncan 2019, p. 132

- ^ a b Laycock, Donald; Voorhoeve, Clemens Lambertus (2019). "History Of Research In Papuan Languages". Linguistics in Oceania. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.

- ^ Wurm, Stephen; Laycock, Donald (1961). "The Question of Language and Dialect in New Guinea". Oceania. 32 (2): 128–143. doi:10.1002/j.1834-4461.1961.tb01747.x. JSTOR 40329311.

- ^ a b Mathews & Chaix 1979, p. 101

- ^ a b c d Mathews & Chaix 1979, p. 102

- ^ MacFarlane, S.; Rawlinson, H. C. (1876). "Ascent of the Fly River, New Guinea". Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society of London. 20 (4): 253–266. doi:10.2307/1799856. JSTOR 1799856.

- ^ "MacFarlane, Samuel". National Herbarium. Retrieved April 28, 2025.

- ^ Keane, John Fryer (1887). Three Years of a Wanderer's Life. London: Ward and Downey. p. 132.

- ^ Foley, William A (2000). "The Languages of New Guinea". Annual Review of Anthropology. 29: 357–404. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.29.1.357. JSTOR 223425.

- ^ Foley, William A (2018). "The Languages of the Sepik-Ramu Basin and Environs". The Languages and Linguistics of the New Guinea Area : A Comprehensive Guide. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. p. 197.

- ^ Mathews & Chaix 1997, pp. 102–103

- ^ Mathews & Chaix 1997, p. 103

- ^ Mathews & Chaix 1997, p. 104

- ^ Mancarella 2011, p. 11

- ^ Jakobson, Roman (1963). "Aspects linguistiques de la traduction" [Linguistic aspects of translation]. Essais de linguistique générale [Essays on general linguistics] (in French). Paris: Éditions de Minuit. p. 64.

- ^ Mathews, Harry (1991). "Le Séminaire improvisé" [The Improvised Seminar]. Cuisine de pays [Country cuisine] (in French). Paris: P.O.L.

- ^ a b Ford, Mark (2003). "Red makes wrong". London Review of Books. 25 (6). Retrieved April 28, 2025.

- ^ a b c d Mathews & Chaix 1979, p. 75

- ^ a b c Mathews & Winckler 1980, p. 113

- ^ a b c d e f Mathews & Chaix 1979, p. 74

- ^ a b c Mathews & Winckler 1980, p. 114

- ^ Mathews & Chaix 1979, p. 116

- ^ Genette, Gérard (2014). Palimpsestes : La littérature au second degré [Palimpsests: Literature at a second level] (in French). Paris: Seuil.

- ^ a b c Mancarella 2011, p. 52

- ^ Duncan 2019, pp. 129–130

- ^ Jullien, Dominique (2003). "La Cuisine de Georges Perec" [The Kitchen of Georges Perec]. Littérature (in French). 129 (29): 3–14. doi:10.3406/litt.2003.1784.

- ^ a b c d e f g Perec 1978

- ^ a b Bellos, David (1993). Georges Perec: A Life in Words. Boston: David R. Godine. pp. 561, 611, 672, 807.

- ^ Fiorletta, Loredana (2020). La dinamica degli opposti : Ricerca letteraria, cultura mediatica e media in Georges Perec [The dynamics of opposites: Literary research, media culture, and media in Georges Perec] (in Italian). Sapienza Università Editrice. pp. 310–314. ISBN 978-88-9377-140-5. Retrieved April 28, 2025.

- ^ a b c Perec, Georges (2003). "Ce qui stimule ma racontouze..." [What stimulates my storytelling...]. Entretiens et conférences [Interviews and conferences] (in French). Vol. 2. Paris: Joseph K. p. 169.

- ^ Mathews & Winckler 1980, p. 111

- ^ Mancarella 2011, p. 67

- ^ Benjamin, Walter (1991). "La Tâche du traducteur" [The Translator's Task]. Po&sie (in French) (55). Retrieved April 28, 2025.

- ^ Apter, Emily (2006). The Translation Zone : A New Comparative Litterature. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 210.

- ^ a b James 2008, p. 141

- ^ a b Duncan 2019, p. 127

- ^ Beebee 2012, p. 90

- ^ Ambroise, Bruno (2008). "L'impossible trahison : Signification et indétermination de la traduction chez Quine" [The impossible betrayal: Meaning and indeterminacy in translation according to Quine]. Noesis (in French) (13): 61–80. doi:10.4000/noesis.1619. Retrieved April 28, 2025.

- ^ Van Orman Quine, Willard (1962). "Le Mythe de la signification" [The Myth of Meaning]. La Philosophie analytique [Analytical Philosophy]. Les Cahiers de Royaumont (in French). Paris: Éditions de Minuit. p. 147.

- ^ Van Orman Quine, Willard (1993). La Poursuite de la vérité [The Pursuit of Truth] (in French). Paris: Seuil. p. 78.

- ^ Van Orman Quine 1960, p. 76

- ^ Duncan 2019, pp. 134–135

- ^ Roubaud, Jacques (1991). "L'auteur oulipien" [The Oulipian author]. L'Auteur et le Manuscrit [The Author and the Manuscript] (in French). Paris: Presses universitairs de France. p. 83.

- ^ Duncan 2019, p. 122

- ^ a b Duncan 2019, p. 134

- ^ Wittgenstein, Ludwig (2005). Recherches philosophiques [Philosophical Investigations] (in French). Translated by Dastur, Françoise; Élie, Maurice; Gautero, Jean-Luc; Janicaud, Dominique; Rigal, Élisabeth. Paris: Gallimard.

- ^ Linsky, Leonard (1966). "Wittgenstein, le langage et quelques problèmes de philosophie" [Wittgenstein, language, and some problems in philosophy]. Langages (in French). 1 (2): 85–95. doi:10.3406/lgge.1966.2336.

- ^ Duncan 2019, p. 140

- ^ Fournier, Marcel (1994). Marcel Mauss (in French). Paris: Fayard.

- ^ Young, Michael W (1984). "The Intensive Study of a Restricted Area, or, Why Did Malinowski Go to the Trobriand Islands?". Oceania. 55 (1): 1–26. doi:10.1002/j.1834-4461.1984.tb02032.x. JSTOR 40330784.

- ^ Firth, Raymond (1989). "Introduction". A Diary in the Strict Sense of the Term. London: Athlone Press.

- ^ a b Van Orman Quine 1960, pp. 58, 129

- ^ a b Laugier, Sandra (2002). "Quine, entre Lévy-Bruhl et Malinowski" [Quine, between Lévy-Bruhl and Malinowski] (PDF). Philosophia Scientiæ (in French). 6 (2). Retrieved April 28, 2025.

- ^ Gellner, Ernest (1998). Language and Solitude : Wittgenstein, Malinowski and the Habsburg Dilemma. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 145–156.

- ^ Albani, Paolo (1998). "Sraffa and Wittgenstein : Profile of an Intellectual Friendship". History of Economic Ideas. 6 (3): 151–173. JSTOR 23722611.

- ^ Malinowski, Bronisław (1923). "The Problem of Meaning in Primitive Language". The Meaning of Meaning : A Study of the Influence of Language upon Thought and of the Science of Symbolism. London: K. Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co.

- ^ Malinowski 1935, p. 11

- ^ Malinowski 1935, p. 12

- ^ Malinowski 1935, p. 17

- ^ Malinowski 1935, p. 14

- ^ a b c d Gervais 2018

- ^ Malinowski 1935, p. 213

- ^ Malinowski 1935, p. 214

- ^ Malinowski 1935, p. 224

- ^ Malinowski 1935, p. 230

- ^ Fitzsimons, Kent (2013). "The Double-Bind of Fictional Lives : Architecture and Writing in Georges Perec's Life, a User's Manual". Once Upon a Place : Architecture & Fiction. Lisbon: Caleidoscópio. p. 171.

- ^ Fabbiano, Giulia (2008). "Déconstruire l'empathie : Réflexions sur l'art magique de l'ethnographe" [Deconstructing empathy: Reflections on the magical art of the ethnographer]. Journal des anthropologues (in French) (114–115): 114–115. doi:10.4000/jda.321.

- ^ Malinowski, Bronisław (1992). Argonauts of the Western Pacific. London: Routledge. p. 43.

- ^ Dangy 2006, p. 217

- ^ Perec, Georges (1989). L'Infra-ordinaire [The Infra-ordinary] (in French). Paris: Seuil. p. 11.

- ^ Dangy 2006, p. 220

- ^ Le Sidaner, Jean-Marie (1979). "Entretien" [Maintenance]. L'Arc (in French) (76).

- ^ Shiotsuka, Shuichiro (2015). "La fonction du savoir imaginaire dans La Vie mode d'emploi de Georges Perec" [The role of imaginary knowledge in Georges Perec's Life: A User's Manual]. Arts et Savoirs (in French). 5 (5). doi:10.4000/aes.312.

- ^ Schnitzer, Daphne (2004). "A Drop in Numbers : Deciphering Georges Perec's Postanalytic Narratives". Yale French Studies (105): 110–126. doi:10.2307/3182521. JSTOR 3182521.

- ^ Baron, Étienne (1937). Géographie générale : Classe de seconde. Programme du 30 avril 1931 [General geography: Second year of high school. Curriculum dated April 30, 1931.] (in French). Paris: Magnard.

- ^ Barthes, Roland (1966). Critique et Vérité [Criticism and Truth] (in French). Paris: Seuil. p. 29.

- ^ Debrand, Nicole (1990). Constance. Paris: Champ Vallon. p. 318. ISBN 978-2-87673-100-4. Retrieved April 29, 2025.

- ^ Merlin-Kajman, Hélène (2003). La langue est-elle fasciste ? : langue, pouvoir, enseignement [Is language fascist? Language, power, education] (in French). Paris: Seuil. p. 116.

- ^ Itaenu, André (2006). "Why the Dead Do Not Bear Names". The Anthropology of Names and Naming. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 65.

- ^ Macfarlane, Samuel (1886). Exploration in New Guinea. Manchester. JSTOR 60231532.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Malinowski 1935, p. 72

- ^ Malinowski 1935, p. 70

- ^ Malinowski 1935, p. 69

- ^ Leach, Edmund (1958). "Trobian Clans and the Kinship Category Tabu". The Development Cycle in Domestic Groups. London: Cambridge University Press. p. 143.

- ^ Mathews & Brotchie 1998, p. 55

- ^ Mathews, Harry (1998). "Mathews's Algorithm". Oulipo : A Primer of Potential Literature. Normal: Dalkey Archive Press.

- ^ Mathews & Brotchie 1998, p. 234

- ^ James 2008, pp. 140–141

- ^ Tillman, Lynne (1989). "Harry Mathews". Bomb Magazine. Retrieved April 29, 2025.

- ^ Collombat, Isabelle (2005). "L'Oulipo du traducteur" [The Oulipo of the translator]. Semen (in French) (19). doi:10.4000/semen.2143.

- ^ a b Bloomfield, Camille; Salceda, Hermes (2016). "La traduction comme pratique oulipienne : par-delà le texte « original »" [Translation as an Oulipian practice: beyond the "original" text]. Oulipo mode d'emploi [Oulipo: instructions for use] (in French). Paris: Honoré Champion.

- ^ Perec, Georges (2003). "À propos de la description" [About the description]. Entretiens et conférences [Interviews and conferences] (in French). Vol. 2. Paris: Éditions Joseph K. p. 237.

- ^ Perec, Georges (April 3, 1981). "Avez-vous lu Harry Mathews ?" [Have you read Harry Mathews?]. Le Monde (in French).

- ^ Harris, Paul (1999). "Harry Mathews's Al Gore Rhythms: A Re-viewing of Tlooth, Cigarettes, and The Journalist". Electronic Book Review. Retrieved April 29, 2025.

- ^ Bénabou, Marcel (18 February 2005). "Exhiber/cacher : Les Oulipiens et leurs contraintes" [Show/hide: The Oulipians and their constraints]. Oulipo.net (in French). Archived from the original on January 14, 2025. Retrieved April 29, 2025.

- ^ Mathews & Chaix 1979, p. 125

- ^ Beebee 2012, p. 87

- ^ Beebee 2012, pp. 89–91

- ^ a b Mathews & Winckler 1980, p. 119

- ^ Beebee 2012, p. 89

- ^ Sabin, Margery (1987). The Dialect of the Tribe : Speech and Community in Modern Fiction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Fulford, Tim (2015). Romantic Poetry and Literary Coteries : The Dialect of the Tribe. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- ^ Eco, Umberto (2008). "Introduction". Esercizi di stile [Style exercises] (in Italian). Turin: Einaudi.

Bibliography

Main sources

- Malinowski, Bronislaw (1935). Coral Gardens and Their Magic : A Study of the Methods of Tilling the Soil and of Agricultural Rites in the Trobriand Islands. Vol. 2: The Language of Magic and Gardening. London: George Allen & Unwin. Retrieved April 28, 2025.

- Mathews, Harry; Winckler, Martin (1980). "The Dialect of the Tribe". SubStance. 9 (2): 52–55. doi:10.2307/3683878. JSTOR 3683878. Retrieved April 28, 2025.

- Mathews, Harry; Chaix, Marie (1979). "Abanika, traditore ?" [Abanika, a traitor?]. L'Arc (in French) (76).

- Mathews, Harry; Chaix, Marie (1997). "Translation and the Oulipo: The Case of the Persevering Maltese" [Abanika, a traitor?]. Brick, A Litterary Journal (57).

- Mathews, Harry; Brotchie, Alastair (1998). Oulipo Compendium. London: Atlas Press.

- Perec, Georges (1978). La Vie mode d'emploi [Life: A User's Manual] (in French). Paris: Hachette.

- Van Orman Quine, Willard (1960). Word and Object. Cambridge: M.I.T. Press.

Secondary sources

- Beebee, Thomas (2012). Transmesis : Inside Translation's Black Box. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Dangy, Isabelle (2006). "Apuena et Appenzzell : Perec au cœur du monde primitif" [Apuena and Appenzell: Perec in the heart of the primitive world]. Cahiers Georges Perec (in French) (9).

- Duncan, Dennis (2019). The Oulipo and Modern Thought. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gervais, Bertrand (2018). "Here not There : la traduction comme métaphore. " The Dialect of the Tribe " de Harry Mathews" [Here Not There: Translation as Metaphor. Harry Mathews' The Dialect of the Tribe]. Cahier ReMix. Cahiers ReMix (in French) (7). Retrieved April 28, 2025.

- James, Alison (2008). "The Maltese and the Mustard Fields : Oulipian Translation". SubStance. 37 (1): 134–147. doi:10.1353/sub.2008.0000. JSTOR 25195160.

- Mancarella, Mariacarmela (2011). Harry Mathews Traduttore : Il gioco e L'identità [Harry Mathews Translator: The Game and Identity] (PDF) (in Italian). Catania: University of Catania. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 1, 2022. Retrieved April 28, 2025.

External links

- Mathews, Harry (September 29, 2006). "The Dialect of the Tribe". Electronic Book Review. Archived from the original on January 20, 2025. Retrieved April 28, 2025.

- Mathews, Harry (March 1, 1997). "Translation and the Oulipo: The Case of the Persevering Maltese". Electronic Book Review. Archived from the original on January 12, 2025. Retrieved April 28, 2025.